Recently another high-profile piece on abandoning statistical significance by Amrhein, Greenland & McShane was published. I have mixed feelings about this, me and my Twitter bubble are mostly like “Another one of those?!”… But how did I get from not doing almost any statistics five years ago to considering myself a cool insider that can look down on a prominent piece by a group of lifelong experts? And what does that say about me?

Spoiler: this post is mostly not about the Amrhein paper.

Start small

I studied computer science which included a mandatory course on probability and statistics. I vaguely remember being OK with probability, shaking my head at all the effort it took to show that averaging numbers makes sense and slightly wondering why we care about “unbiased estimators”. The lectures on basic hypothesis testing felt esoteric and I couldn’t wrap my head around it. As the examination neared, I did other stuff students do and ended up not even reading the hypothesis testing part of my notes. Of the four exam terms this year, the one I attended was the only one to not have any questions on hypothesis testing. I barely passed and quickly forgot. Later, I took a machine learning course and a neural networks course, but I didn’t notice any connection to the statistics stuff.

Around 2012, when finishing my masters I realized I have some data on the time various AI agents took to solve a task and I need to analyze them. My advisor recommended I read “Statistics Explained: An Introductory Guide for Life Scientists” by McKillup. This felt like a revelation. Suddenly some of the things I’ve heard about before made sense and I could understand why you would use a t-test.

But I didn’t really have two groups and couldn’t figure out how to extend the ideas from McKillup to my tasks, so I got a consultation with a statistician and I first heard of “linear models”. I didn’t understand what I was doing, but by trial, error and Googling I managed to call glm with semi-sensible arguments and I got a bunch of p-values, lots of them even below 0.05! Being a confident guy, not understanding what a linear model is didn’t prevent me from writing things as:

… we consider lack of rigorous statistical analysis in game AI experiments an issue in the field.

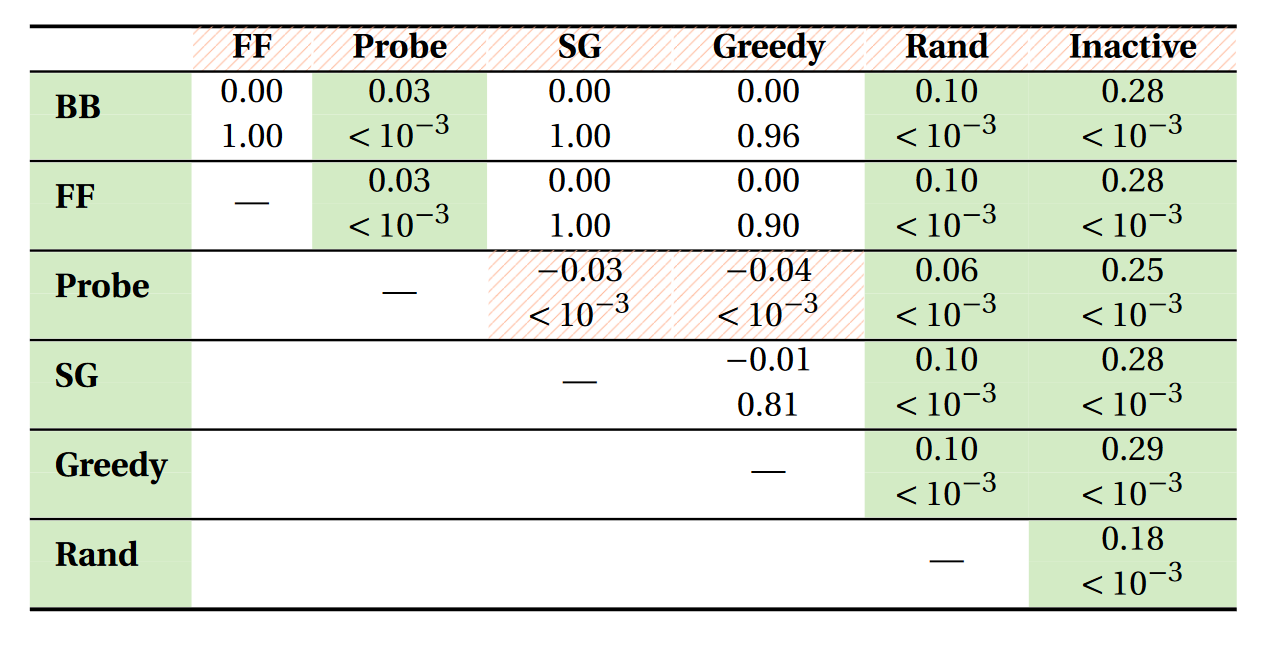

I was proud of myself, I even showed a set of “nice” tables with effect sizes, p-values and highlighted significance:

Effect size on top, p-value below. Doesn’t that warm your heart?

Effect size on top, p-value below. Doesn’t that warm your heart?

Looking at the paper now, there is at least a faint relief that I did correct for multiple comparisons.

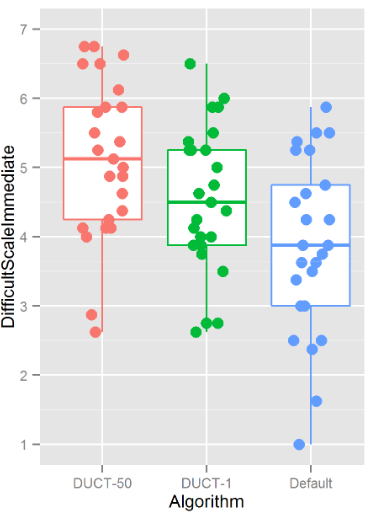

The New Statistics

I didn’t need a lot of statistics for a while, but then, around 2014, a colleague sent me a link to The new statistics: why and how by Cumming. This felt like a revelation. I started hating p-values and thought everybody should preregister everything. I didn’t do a lot of empirical stuff at the time, but in 2016, I wanted to compare how people felt playing against several types of AI in a game. And I wanted to do it the The Right Way™. I’ve used aspredicted.org to preregister my study (just hours before I started collecting data). I made all the code and data available. I plotted individual data points. I averaged several Likert responses and used confidence intervals of multiple pairwise t-tests on those averages. Nothing could stop me, I knew how statistics should be done.

Bayes

After PhD in mid 2016, I changed fields and started doing bioinformatics. Soon, I noticed that statistics might play a vital role in my new job, but everybody in the lab admitted they don’t really know anything about it. I googled the weird phrases that appeared in the literature I was digesting and I started reading random stuff that popped up. I realized there is a connection between least squares and normal distribution. I noticed some people tend to use the word “Bayes” a lot and they say nice things about it. My colleague from earlier told me that New statistics is outdone and all the cool kids use Bayes factors now. Then I stumbled on Andrew Gelman’s blog.

This felt like a revelation. In retrospect, this process of repeated revelations probably should have raised a red flag or two.

Image courtesy of XKCD: https://xkcd.com/1027/

Image courtesy of XKCD: https://xkcd.com/1027/

Anyway, I’ve bought in with all the enthusiasm of a new convert. I’ve read several years of Andrew’s blog in full and I started to dislike Brian Wansink and Amy Cuddy. By mid 2017, I’ve attempted rewriting the gene expression model I used into Stan and I failed terribly. I tried to push Bayes in metatranscriptomics and failed. I tried analysing single-cell RNA-seq with Bayes and failed. I filed my first pull request against Stan’s codebase and later write my first actually useful model. It is telling that to write this post I’ve cannibalized a stub I pushed to GitHub a year ago, which had the title “Go Bayes: Why and how”.

I learned new stuff and was amazed, the stuff made sense! I finally took time to understand this “linear model” thing and become fluent in which distributions there are and what is a likelihood. I read The 100% CI, Data colada and others. I started to have strong opinions on preprints and academic publishing. I was on a fast trajectory to become an obnoxious critic of statistics in other people’s work and a loyal follower of the various heralds of scientific reform.

Beyond

In some sense, Twitter has prevented that. I can’t exactly put my finger on it, but most likely, it was following Danielle Navarro that showed me a different social bubble. Some comments on Andrew’s blog were also certainly an influence. Whatever the tipping point, words like “kindness” and “community” entered my thinking about science. In some sense this was an easy shift as I have long experienced the power of being kind first-hand through my involvment with the Czech scout movement. I am a bit ashamed it took me so long to realize it could apply to science as well.

From a different angle, I noticed Daniël Laken’s blog and read up on Deborah Mayo’s work. And they made sense - who would have thought that frequentists weren’t all evil monsters delaying the inevitable victory of the One True Gospel of Reverend Thomas Bayes? Maybe I still have a lot to learn about methods and statistics and everything around that?

I worked on improving my knowledge of philosophy of science and quickly started feeling like it’s all a bit more complicated than I thought (surprise). These days, I work hard to include as many people as I can in constructive discussions about how to improve our methods. I am trying to find ways to make statistics understandable, to convey what models do in precise, but approachable language. I’ve stopped shaming people for their code or stats. I’ve attempted doing constructive post-publication peer review. I try to be a good mentor to anyone who asks for guidance I can provide, but not give unsolicited advice. I aim to talk less, listen more and more readily say “I don’t know”. And it’s hard, harder than the math part (which is still very hard). But it needs to be done - my current understanding is that people, communities and institutions are the most important part of any effort to improve science.

Around this point, it would be useful to clarify what this story is about. Is this a cautionary tale, telling how manifesto’s and rally cries can make people overzealous? Is this a story about my failure to see the bigger picture? Or is this an ecouragement that pieces with strong opinion can make people grow and continuously improve? Frankly, I am not sure.

It is true that I got to the point where I am through calls to action. I was wrong times and again, but everytime I learned new stuff and became at least a little less wrong - I finally came far enough to notice there might not be an end to this journey, no final and definitive answers, just a life spent trying hard to improve what we can.

And it is also true that I’ve been foolish many times in the past. I was quick to absorb new statistical religions, but I was wrong and sometimes annoying and likely also causing harm. And that’s something that makes me wary of the calls for reform, even though I think the Amrhein paper is well worded and better than most other rally cries I’ve read before. I am certainly sympathetic to the claim that a part of the problem with science is not that people don’t listen to statisticians, but that they listen all too well.

I don’t have answers, but I currently believe the way we treat each other and the way we frame our discussions is in at least a similar level of crisis as our statistics. This journey is not over and many obstacles still lie ahead.

Thank you

However, I am certain that a lot of gratitude is due. I want to give my sincere thanks to people that helped me on my journey towards statistics and especially to people who work hard on improving what we do. To those that inglamorously solve one small problem after another. To those that sincerely try to improve their methods regardless of skill level. To those that care for each other and build islands of trust and kindness. Thank you very much.

I thank Danielle Navarro for alerting me to how much kindness matters in science and generally being a role model in writing and thinking.

I thank Dan Simpson for his relentless fear of being wrong and for being his fabulous self.

I thank Michael Betancourt for the deep insights into the math that I struggle to digest.

I thank Hadley Wickham for the idea of “Teaching Safe-Stats, Not Statistical Abstinence” and - obviously - for tidyverse.

I thank Berna Devezer for highlighting areas of philosophy of science that I could’ve missed otherwise.

I thank the Stan community for all the feedback and help in learning and also for the opportunity to give back.

I thank everyone who I forgot to include here - I am sorry that my memory is so weak. You are all great and I am in awe and feel priviliged to be able to learn from you.